Every second, around 4 million tons of solar mass are converted into heat and radiation. This energy is generated in the sun's core in what is known as the proton-proton cycle. Extreme conditions of 15 million degrees Celsius and a pressure of 150 billion bar prevail there, where the atomic nuclei are pressed into each other.

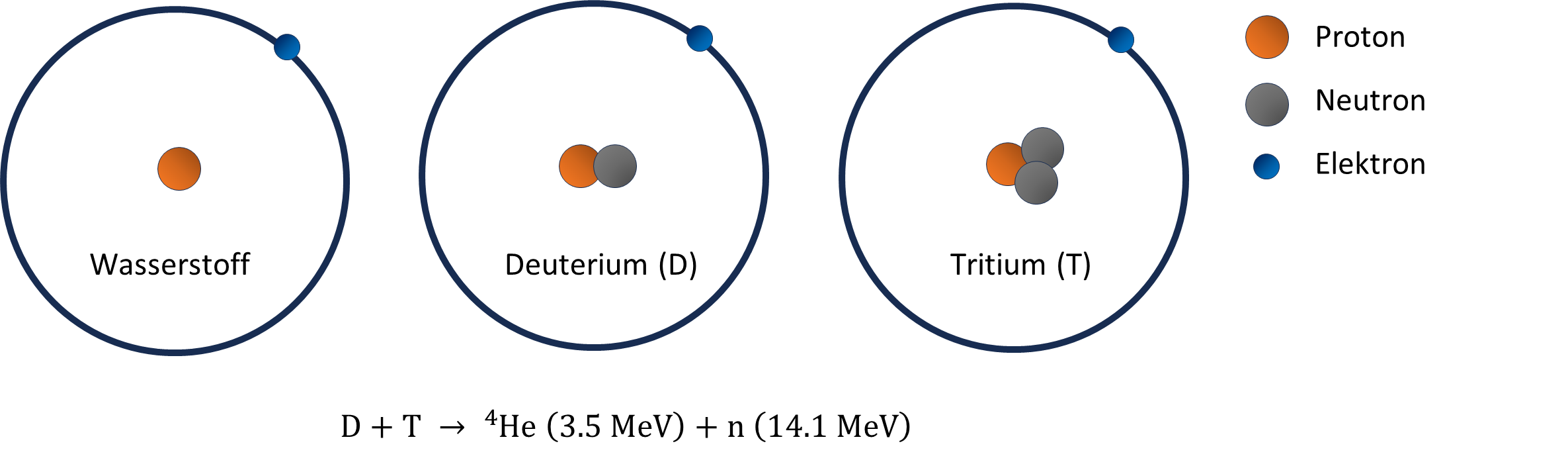

As such conditions are difficult to reproduce on Earth, higher temperatures at lower pressures are used. The reaction is produced at temperatures of around 150 million degrees Celsius. In addition, instead of protons, the isotopes of the hydrogen atom deuterium and tritium are used as starting materials, which fuse more easily than the hydrogen in the sun.

But how are such extreme temperatures generated on Earth and why doesn't everything that comes into contact with it melt?

When hydrogen gas is heated, the positively charged ions separate from the negatively charged electrons. This is called a plasma. Such a plasma can then be controlled by magnetic fields. In a fusion reactor, an external magnetic field is controlled in such a way that the plasma inside does not touch the walls - it is magnetically confined.

If you manage to control the magnetic field, the plasma and all other necessary components well enough, you create a stable state in which the hydrogen fuses and generates heat. This heat ensures that the fusion process does not stop and the heating elements can be switched off. Excess heat is released via the reactor wall and is used to generate electricity.

Fusion research has made great progress in recent years. However, to date, the energy generated, although close, is still less than the energy used for the process. 1

Tokamak

The simplest arrangement for a magnetically confined plasma is a cylinder. Here, however, the plasma would run out at both ends. It therefore makes sense to bend this cylinder into a donut-shaped ring - the tokamak.

In addition to the coils along the donut, a coil inside the donut and two coils above and below the reactor, which control the vertical movements of the plasma, are needed to control the plasma.

However, this simple design also has disadvantages. Controlling the plasma is extremely difficult. The reactor can only work in pulsed mode. This means that the plasma must be reheated again and again at certain time intervals. In 2022, the EAST reactor in China set the record with a pulse duration of around 18 minutes. 2

Spherical tokamaks are also increasingly being used in newer setups. These apple-shaped superstructures have the advantage of a more compact design and better plasma confinement. 3

Stellarator

In contrast to the pulsed operation of the tokamak, the reactor design called stellarator offers the possibility of continuous operation. The coils are designed in such a way that the plasma is additionally twisted. The design and manufacture of the asymmetrical coils used are very complex, but offer the advantage of simple control and monitoring of the fusion process.

Innovation & progress: a selection of current projects in focus

ITER

China, the European Union, India, Japan, Korea, Russia and the United States are working together on the ITER tokamak project. This has been under construction in Cadarache, France, since 2010 and is due to start its deuterium-tritium operating phase in 2039. 4

DEMO

The DEMO demonstration power plant is the successor project to ITER. The transition from ITER to DEMO transfers the project from a scientifically oriented, laboratory-based program to an industrial and technology-oriented program. The central requirement of the project is the generation of electrical energy with an output of between 300 and 500 megawatts as well as working in a closed fuel cycle in which the spent tritium is reprocessed. 5

Wendelstein 7-X

Wendelstein 7-X at the Max Planck Institute in Greifswald, Germany, is the world's largest stellerator. It consists of 50 specially shaped superconducting coils. It produced plasma for the first time in 2015 and has so far achieved a maximum operating time of 30 minutes. The Max Planck Institute offers a virtual visit to the facility on its website.6

ASDEX Upgrade

In addition to the stellarator, the Max Planck Institute also operates the ASDEX Upgrade tokamak in Garching near Munich. The "Axially Symmetric Divertor Experiment" went into operation in 1991 and is intended to investigate core questions of fusion research under power plant-like conditions and to develop the physical foundations for ITER and DEMO. The Max Planck Institute also offers a virtual visit to the facility on its website. 7

Sources:

1 J. Ongena, R. Koch, R. Wolf, H.Zhom, "Magnetic-confinement fusion", Nature Physics (2016), 398-410

2 EAST demonstrates 1000-second steady-state plasma

3 Spherical Tokamak | Efficient Design, Energy Output & Research

4 ITER - the way to new energy

5 DEMO - EUROfusion

6 Wendelstein 7-X

7 ASDEX Upgrade

Your contact

Bayern Innovativ GmbH,

Bayern Innovativ GmbH,